Paul Heintz: NAFURA

Solo show

gb agency, Paris

September 2 - October 7, 2023

For his second solo exhibition at gb agency, Paul Heintz presents his most recent film, NAFURA (2023). Fascinated by Jeddah’s huge water fountain in Saudi Arabia, that is said to be the highest in the world, he wanted to question the relation between the control of water and political authority. In this project, Paul Heintz flirts with a new form of narrative, exploring, for the first time, a proper fictional structure. The three girls that lead the film add their own political and poetical positions to his, settling this film in the continuity of his work.

The objects in the mirror are closer than they appear

by Carin Klonowski

Nafura - or fountain in Arabic - is the title of Paul Heintz’s latest film, presented as part of his eponymous exhibition at gb agency. It’s a wandering, nocturnal fiction about three young women in the city of Jeddah, dominated by the largest artificial geyser in the world, the “water jet of King Fadh”. In this fable-roadmovie, they seek out the source of the water, turning the spectacular and fascinating image of its gush into a demonstration of power and control.

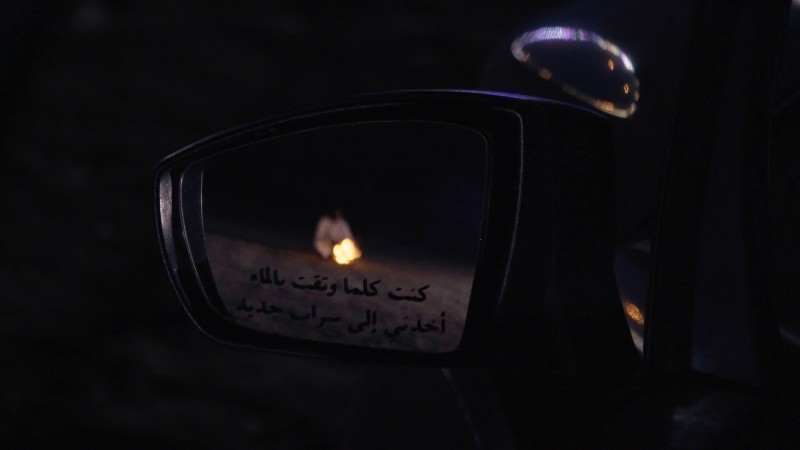

At a glance through the rear-view mirror, reality is much closer than it seems.

Its emergence is part of an incidental movement, a trajectory from the fountain towards the young people who live around it and with it, in the tangle and reversibility of reality and fiction. How can we talk about what we can’t talk about openly, because it’s too risky, and because we’re - in this case - too far away from it?

Headlights on.

Over the film’s three protagonists, young Saudi women in search of entertainment and freedom to counter the boredom of a warm winter’s evening. We follow them as they wander, hear them talking about love, singing and joking. They play, but their game becomes serious. As their car slides down the asphalt, they speak the words and practices banned by the oppressive, capitalist, patriarchal and religious powers that be, replacing them with the symbolic word nafura.

They smoke, playing with fire while their image burns.Their faces are literally and figuratively overexposed and radiate light, making it impossible to identify them. Between the end of the film’s production and its screening, the danger of appearing in the image became too great. Their faces and voices had to be concealed to guarantee their safety in a part of the world where breaking the law is violently punished, whether or not it’s through acting.The moment of freedom granted to them by the film has been overtaken by the appalling reality of censorship and surveillance. Just as they enunciate the forbidden behind the apparent splendour of the fountain, their incandescence protects them in an outburst of visibility.

The real and contextual tension of the image is played out at its very heart.A disappearance that must be dialectically reversed to prevent it from becoming deadly: hiding in plain sight.The image of faces, like three glimmers of light, volatile and rebellious, becomes as difficult to fix as a reflection in moving water, and the embodiment of a possible emancipation. The visual effect offers them a fleeting, tenuous opportunity to question an authoritarian system and to enter its (hydraulic) machinery.

A machinery we will never really see.The highly seductive shots of the water gushing quickly give way to its intricacies, in sequences mixing 3D animation and photogrammetry that punctuate the film and simulate what the fountain’s pipes could be.Waste and particles float in the middle of pipes that gradually turn into the ruins of buildings with graffitied walls:

Evacuation - Evacuation - Evacuation.

“Evacuation is a word that makes me cry”.

The real overflows, forcefully, through the artifice of computer-generated images, recounting a whole system that cannot be filmed or told, or even captured by the mere sight of the water jet. From the destruction of entire neighbourhoods to make way for shopping centres, to the submergence of the city due to the lack of an efficient drainage system and the absence of building regulations, not to mention Lake Al Musk, filled with waste water that has repeatedly threatened to spill into Jeddah.

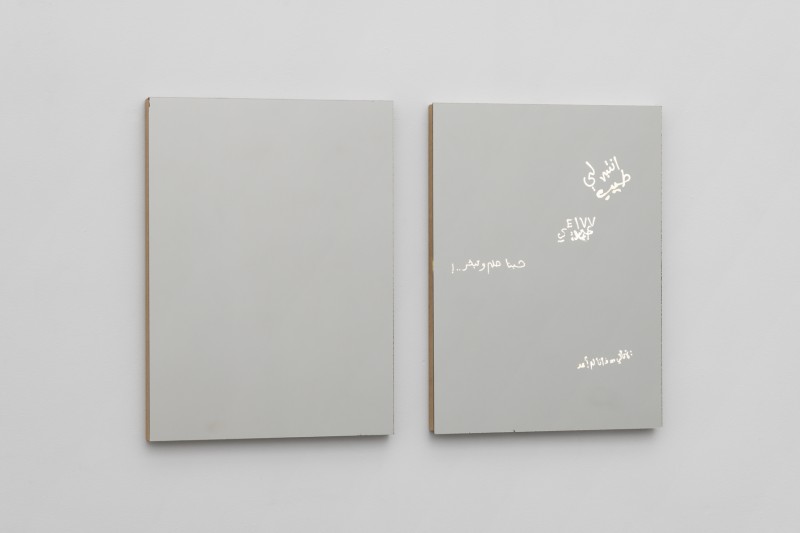

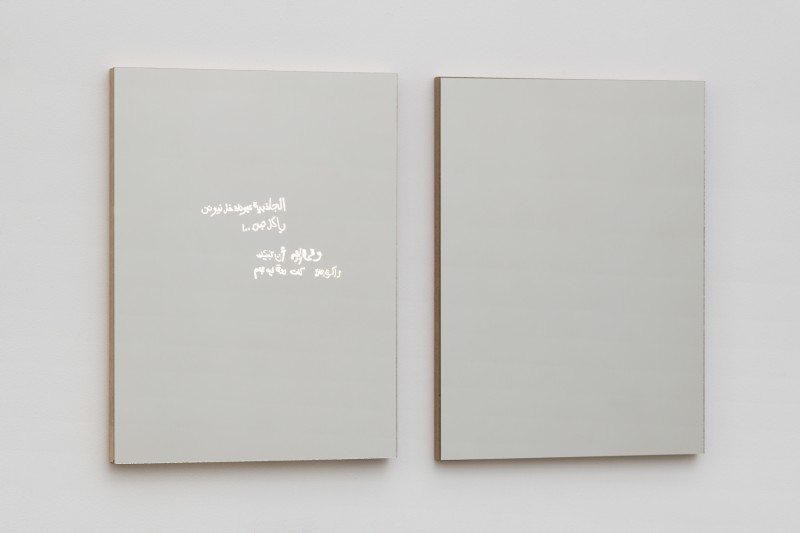

An overflow where the political charge exceeds the image, where the very projection of the film exceeds its frame. Facing it, is a line of mirrors in which it is reflected.A raw material used to make rear-view mirrors, these shimmering backlit surfaces are engraved with graffiti in Arabic, and punctuate the exhibition space like the neon signs and casinos lining the motorway.The poetic appearance of the composition of the texts and their glow in the dark nevertheless have a sombre tone: surveillance, expulsion, loss of reference points and memory, unquestionable decisions - all testimonies that the artist was confronted with during his filming.The mirrors take on the appearance of steles, and the removal of the one-way glass leaves a void, heavy with meaning.

In the blind spot and beneath the surface of the image - superficial and dazzling - of the fountain, a violence and a grim reality, hidden in the cesspool of its pipes. At its end lies a dark cavern with a floor bathed in opaque water. A door opens, bringing with it the possibility of sabotage, seemingly unintentional. The fountain silently runs dry.

In this exhibition, what is said and what is seen is under constant pressure.A state of vigilance and control, to which Paul Heintz responds with an interplay of reflections, glares, changes of focus and of visual registers.The constrained erasure of the image is resisted by its deployment in spatial and temporal depth, between the horizontal unfolding of the fictional narrative roadtrip and the almost documentary jumps that occur in it. And in this perpendicular order, the sinuous and lively journey of the three characters. All these narrative and visual elements reveal oppressive forces at work, turned on their head by the fragile but enduring poetic power of youth and its affects, of light and water.

A shot seen through a rear-view mirror. Instead of the usual warning, it reads: “Every time I thought I found water, it led me to a new mirage”.This inscription, taken from the poem Spending the Night in Salt Trenches by Zaki Al Sadeer, is even more telling about the indeterminacy and power of the image.The ambivalence of what it reveals as much as what it conceals, the possibility and necessity of overturning its mechanisms and illusions in order to reveal a space for expression and desire.