Dominique Petitgand: L'élément déclencheur

A solo show by Dominique Petitgand

gb agency

From February 4 to March 19, 2016

L’élément déclencheur (The Blastoff Factor)

The immersive nature of sound—as it expands and envelops—is often remarked upon. “It even turns out that ears don’t have eyelids”1, and that there’s no escaping from sound. We’ve all done it, closed our eyes and felt the slight vibration that follows. With ears wide open, I get a similar vertigo when experiencing works by Dominique Petitgand. And isn’t “The Internal Ear“—which also happens to be the title of an earlier Petitgand exhibition – the basis of our equilibrium?

-

“Il se trouve que les oreilles n’ont pas de paupières” (It turns out ears don’t have eyelids) is of course the precise title of an adaptation by the composer Benjamin Dupé of an essay by Pascal Quignard “La haine de la musique” (The hatred of music), published in 1996 by Calmann- Lévy. ↩

To be sure, years have passed since I started listening to the artist’s works— records, concerts, exhibitions—and I’m familiar with the restricted collection of recordings from which Petitgand mixes his arrangements and constructs his sound pieces. And so, I recognize the handful of voices that appear and which, oddly, have become dear to me, almost companions. To be sure. And yet that feeling of vertigo resurfaces each time, though it also varies. Depending on the work, its placement, acoustics, the artist’s cut, his ear during production, my own which changes from one visit to the next according to my way through an exhibition, my energy and attention—and it’s all by way of another editor, that of the body and the spirit.

The apparent familiarity of the sounds, voices, speakers, and their intentionally human scale establish a tranquility that’s essential for the development of the story: like shortcuts:1 on a well-worn path, Dominique Petitgand uncovers the strategies we use to fill our memories, perceptions and conversations, to position events and assertions, to situate them in place and time, creating fresh narratives, occasionally inverting cause and effect, and the way things transpire.

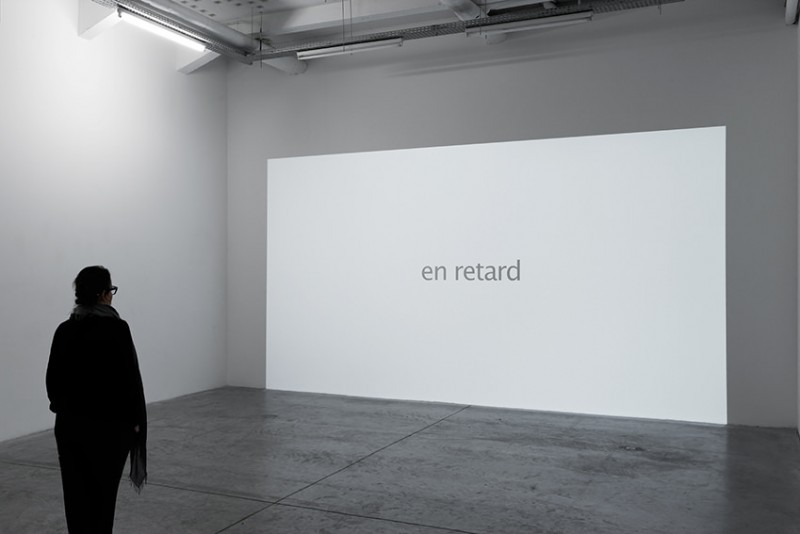

“I waver”

In the main space, to the right of the staircase, phrases appear on the wall in black letters against a white background—the projection of the video ‘Les lettres blanches’ (The blank letters), 2016. Is this a journey across the psyche: some acts in the first person singular, some fragments of the human body, landscapes, like moments surrendering to the details, a listing of things observed, heard, that we tell ourselves and to ourselves alone? A deceptive feeling of precision, engraved statements giving the impression of experiences, all talked about; and just as quickly, an absence of reference points or meaningful context, and a collection of logical propositions that go wrong. And then we’re lost. We try to anticipate the next idea, filling in the blanks, but still another evolves in all incongruity, and we’re left hanging, among the voids that now we can even see. Not those silences that we fear in conversation, but real voids—blank screens. Images of silence that fill the sound works by Petitgand. And propel us to practically study the walls searching for the nuances and the nature of silence. And then they appear, made real through the varying duration of their projections. But this impact isn’t from the illogic of collage, and that’s what tops off the conundrum and instills the expectation: after the surprise, the simple display of what’s written takes and guides the visitor by the hand. We waver, but we don’t fall.

The journey continues, hinted at with a few markers along the way:2 while the brain itself wanders through space, roaming its “memory palaces” like an orator repeating his lines.3 These are “memory palaces” with rooms hardly less empty than the spaces filled by Petitgand: rationales are devised, shortcuts to the psyche are (again) used, and mainly his thoughts are revealed. Breathing and reflection follow the beat of the same pulse, at the pace of footsteps. And listening occurs in harmony. Yet surprisingly, there is a dissonance between the pulsing of the projected text and what we think of as the cadence of the “I.” What is “heard” in the written text in the absence of a voice—rare itself in the work of Petitgand—is as much the diction (a chant from the pulsing projections) as what is “said” by the text itself. Which, by the way, doesn’t “say” but rather immerses the visitor in a stream of consciousness, reinforced by the black letters on the white background.4 Different time-spaces—the “I” of the artist, visitors, of the exhibition, the written or projected texts, electronic sound, other work seen throughout the exhibition—pile up or recede, triggering imbalances. We waver, but we don’t fall.

“I still waver”

Though we do flinch. From the sounds and vibrations coming out of the hefty speakers on the floor on either side of the picture rail separating the gallery. These are deep sounds, making real the electronic path that separates them from the visitor. It may be a droning ambient sound, but in reality it punctuates the space with jolts rather than submerging it. Fragmented, on then off again, the sounds seem to expand at the rate of the projection of video text. In turn, the video blanks and phrases trigger fragments of powerful surges whose duration is precisely timed to the projection, as are the silences that frame them. It’s not clear if the sound triggers the appearance and disappearance of text, or the other way around. Little by little signs of cause and effect begin to appear, though it defies logic since aside from the visitor there is no other élément déclencheur.

In addition to listening and managing his way through the exhibition (apart from the artist’s path), the visitor begins to get the impression of “being” the élément déclencheur—like with motion sensor lights or radio reception that gets interrupted. The visitor is literally at the center of ‘Con-trac-tion, con-signe’ (Con-trac-tions, Ins-truc-tions), 2016, in the middle of a ping pong game between two speakers, between two voices whose words and phrases are literally being deconstructed. It’s a rapid fire and tense match, it twitches, it whistles. It strikes the way voices strike on syllables that have been displaced. It tenses up, it stretches out. The editing is uneven, the position of the visitor relatively static though hardly at ease: trapped by both voices bouncing off each other, thwarting the visitor’s words, rendering him breathless, controlling his own breathing and listening according to what he hears. And if he does regain the control to listen, actively, with ‘Elle me parle’ (She speaks to me), 2016, the visitor is no less an outsider to what is going on, a helpless listener. But truly helpless? At once silenced, (the intercom only works one way), there are nonetheless eyelids for the ears: a finger on the button of the intercom can turn on and off the sound, controlling the duration, creating long or short bursts—blinking the ears, or closing them.

Pressing the button opens the door to another space, an inaccessible one. An “elsewhere.” A woman is having a conversation with a mysterious interlocutor whose voice (as is always the case with Petitgand) we never hear. The woman is busy while she speaks, perhaps in the kitchen. Ultimately that doesn’t matter. What is important is the degree to which the journey of sound joins that of the body and the psyche. As Lacanians would say “to hell with etymological truth”—in the terms interlocutor and elocution, there is location, and locus.

And speaking of etymology, the French verb “déclencher” (to set off, to trigger) comes from the noun “une clenche” which is French for the latch of a door handle. So by releasing the latch and opening the door, “déclencher” means moving into a different space, an elsewhere. Thus it shouldn’t be a surprise that in French slang the word also means to bitch or rant: opening the door of words.

Marie Cantos

-

“je prends un raccourci” (I use a shortcut) is also one of the texts visitors see while watching the projection in the installation “Les lettres blanches.” ↩

-

For example: “sur la pelouse,” “je me déplace,” ou “je rebrousse chemin” (on the grass, I move, or I turn back). And even “la lumière baisse” (the light dims) at the end of the piece, as if to show how time passes from wandering this way. ↩

-

L’ars memoriae, “the art of memory” also known as the Method of Loci is a mnemonic device from antiquity and taught for centuries to orators in universities: memory palaces enhanced memorization through the visualization of images in a specific location. Items to be remembered are associated with specific physical locations along a specific route which is familiar and easily recalled. Items are thus remembered by mentally following the route. ↩

-

This arrangement is above all meant to differentiate the text from the subtitles the artist includes in installations abroad, but at the same time refers to the intimacy of reading (as opposed to white letters on a dark or colored background in film or other images), and it also allows contact with the imagination before becoming conscious of it. ↩